hetic fibers to control cracking and improve impact resistance, while decorative or residential slabs may use micro-fibers to limit surface hairline cracks and dusting. By distributing reinforcement throughout the concrete, fibers are ideal in applications focused on crack resistance and durability rather than carrying heavy structural loads.

What Is Rebar Reinforced Concrete?

Rebar-Reinforced Concrete is concrete strengthened with steel reinforcing bars (“rebar”) or welded wire mesh placed inside the formwork before pouring. The steel bars, typically arranged in grids or along critical locations, act as an internal skeleton that carries the tensile forces that plain concrete cannot handle well. Concrete has high compressive strength but very low tensile strength – roughly only 10–15% of its compressive capacity. By embedding steel rebar in the tension zones (such as the bottom of beams or middle of spanning slabs), the composite concrete member gains the ability to resist bending and stretching forces without cracking apart. The concrete grips the ribbed steel tightly (due to chemical bond and friction), so when the concrete wants to crack under tension, the rebar holds it together and bears that tension.

The main purpose of rebar is to provide structural load-bearing capacity in tension. Steel rebar has a high tensile strength and a similar thermal expansion coefficient to concrete, making it an ideal partner to work with concrete under a range of conditions. In practice, engineers design the size, number, and placement of rebars according to the loads the structure must support. Rebars are placed in specific patterns (like grids or cages) and at certain cover depths, following building codes and structural calculations. For example, in a beam, rebar runs near the bottom to resist sagging tension, and over supports to resist uplift (negative moment) tension. In columns, vertical rebars take axial tension/bending and ties or stirrups provide confinement and shear resistance.

Rebar-reinforced concrete is widely used in heavy-load and structural applications. Typical uses include foundations and footings, load-bearing columns and beams, suspended slabs and balconies, bridge decks and piers, and any critical structural element that must support significant loads or stresses. For instance, multi-story buildings and bridges rely on rebar to handle tensile forces during normal loads and extreme events like earthquakes. Steel reinforcement is often mandatory in seismic-resistant design because it adds ductility – the ability of a structure to deform without sudden failure, absorbing energy during earthquakes. In short, wherever concrete must carry substantial tension or flexural loads safely, rebar is the go-to reinforcement to ensure the structure’s strength and stability.

Fiber Reinforced Concrete vs Rebar

When comparing fiber reinforcement and rebar, it’s important to recognize that each excels at different aspects of concrete performance. Below, we break down the differences across several key criteria:

1) Scope of Application

Fiber: Best suited for projects where crack control and surface durability are the primary goals, rather than maximum structural load capacity. Fibers shine in slabs-on-grade, thin sections, pavements, precast panels, shotcrete linings, and overlays – cases where distributing reinforcement throughout the concrete helps reduce shrinkage cracking and improve toughness. For example, a large slab or pavement with fibers will have a fine network of micro-reinforcement to resist shrinkage and thermal cracks, thereby maintaining a smooth surface with fewer visible cracks.

Rebar: Best for major load-bearing structures and structural members that must support significant weight or forces. This includes beams, columns, suspended floors, retaining walls, and foundations in commercial buildings, bridges, and other infrastructure. Rebar is the standard choice when an engineer needs to ensure a concrete element can carry high tensile or bending stresses (as dictated by building codes). In applications like high-rise construction or bridge girders, steel rebar provides the necessary reliable strength and ductility to handle those loads.

Typical examples: A warehouse floor or residential driveway might use fiber reinforcement to minimize shrinkage cracks and improve impact resistance, whereas a bridge span or multi-story column will use a cage of steel rebar to achieve the needed structural strength. In practice, it’s common to use fibers for general crack control in slabs or precast units, and use rebar for critical load paths. Each method targets a different performance outcome: fibers for distributed crack prevention, rebar for focused structural capacity.

2) How Each Reinforcement Works

Fiber: Works as a distributed reinforcement that spreads throughout the concrete matrix. Because fibers are mixed uniformly in the concrete, they “bridge” cracks everywhere they form, from the moment the concrete is fresh to when it’s hardened. This omnipresent network of fibers intercepts micro-cracks very early, preventing them from growing. Essentially, fibers turn the brittle concrete into a composite that has many tiny reinforcing elements randomly oriented in all directions. This improves the concrete’s toughness (energy absorption) and post-crack behavior – when the concrete does crack, the fibers keep the pieces interlocked and able to carry some load instead of falling apart immediately. The term often used is omnidirectional reinforcement, since fibers offer support in any direction it’s needed.

Rebar: Works as discrete reinforcement that must be strategically placed in specific locations (usually where tensile stresses are expected). Rebar is typically laid out in a grid or along certain lines so that once the concrete hardens, the steel bars will take tension when the concrete element is loaded. It acts like a skeleton or spine: the concrete grips the bars, and under load the rebar carries tension while the surrounding concrete carries compression. Because rebar is only along particular paths, it provides very high strength along those paths but does little for areas in between bars until the concrete cracks and engages the steel. We often describe this as placed reinforcement, as workers must install the bars or mesh exactly according to the design drawings. The outcome is a composite with well-defined load paths – the steel and concrete work together to resist forces where the engineer has predicted they will occur.

On site, this difference means fibers are simply mixed into the concrete (simplifying placement), whereas rebar requires a separate fabrication and installation process (cutting, bending, tying in place) before concrete placement. Fibers create an internal mesh as the concrete sets, whereas rebar creates an internal skeleton that the concrete is cast around. This fundamental distinction – random 3D reinforcement vs. planned 2D/linear reinforcement – underlies many of the other differences in performance and construction between fiber and rebar.

3) Crack Resistance and Surface Performance

Fiber: Excellent at controlling early-age and shrinkage-related cracks, and at keeping crack widths small at the surface. Because fibers form a microscopic web throughout the slab, they are very effective in preventing plastic shrinkage cracks (those that can appear within hours of pouring, as water evaporates) – something rebar cannot do since rebar isn’t effective until the concrete hardens. Fibers also reduce drying shrinkage cracking and thermal contraction cracks by distributing the strain across many tiny fibers. The result is a tighter crack pattern: if cracks occur, there tend to be more of them but each is much smaller in width. This is beneficial for surface durability and appearance. A fiber-reinforced slab often has less visible cracking and less risk of cracks turning into potholes or spalls. Additionally, fibers help reduce surface issues like crazing and dusting by strengthening the cement paste near the top surface, yielding a harder, more uniform finish. With fibers, joints in slabs can sometimes be spaced farther apart as well, since the fibers control intermediate cracks – meaning fewer joints and a smoother overall slab surface. Overall, fibers are known to preserve the concrete’s appearance and reduce maintenance: they keep cracks so small that they don’t readily admit water or stand out visually.

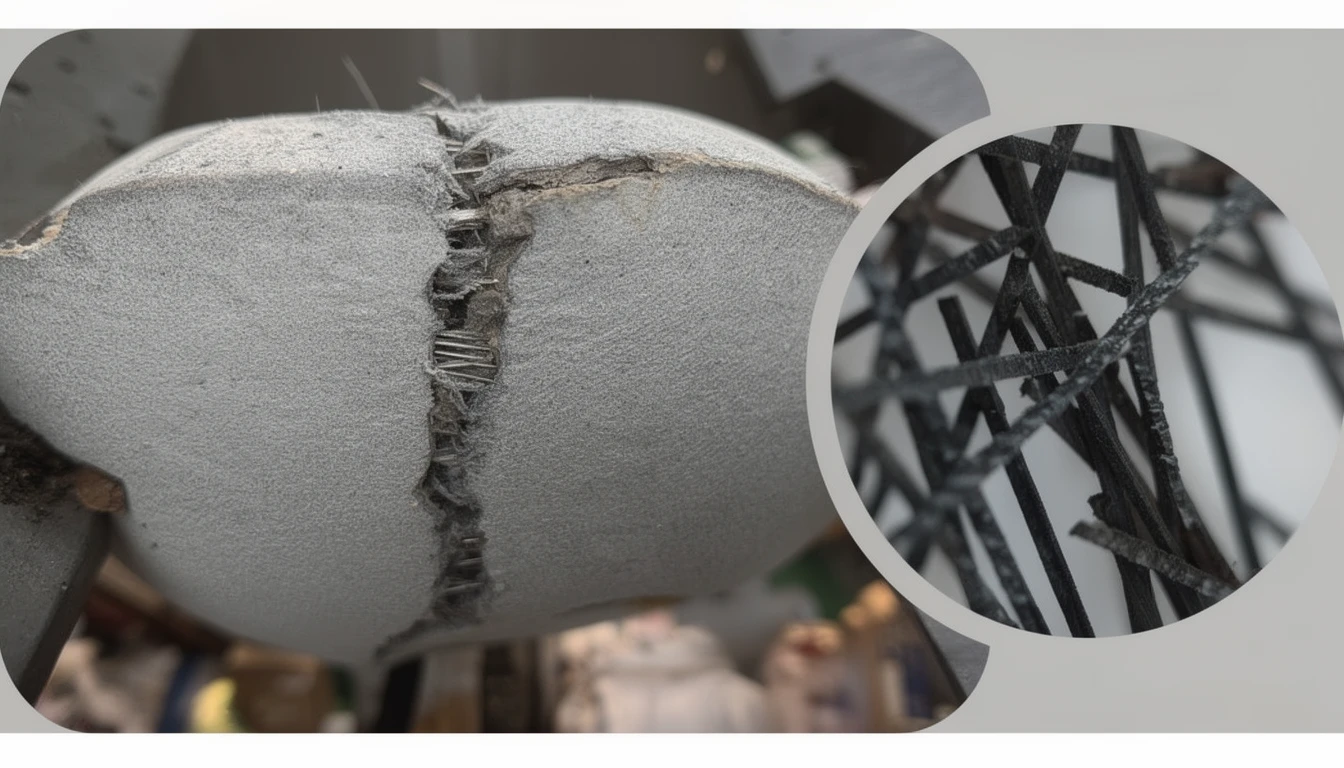

Rebar: Provides crack control primarily for structural cracks under load, but it does not prevent micro-cracks or shrinkage cracks from forming in the first place. Rebars will limit the propagation of cracks once the concrete is under service loads – for example, if a crack forms in a rebar-reinforced beam, the rebar holds the crack faces together so the crack remains narrow and the member doesn’t fail suddenly. In fact, rebar-reinforced concrete tends to exhibit a few cracks at predictable locations (like mid-span of a beam) when heavily loaded, but those cracks are kept to a moderate width as long as the rebar is yielding (engineers design for a maximum crack width for durability). However, rebar is not effective against early-age shrinkage cracks, so such cracks can occur uncontrolled if other measures (like fibers or curing) aren’t used. In slabs, wire mesh or rebar can control long-term drying shrinkage cracking to some extent by distributing the tension, but fibers are often better for the fine cracks. With rebar alone, any cracks that do occur may be wider than with fibers (since there are fewer reinforcement points across the slab) – though rebar ensures the cracks do not threaten the structure’s integrity. On the surface, a rebar-only slab might show fewer cracks but each could be more visible (wider) if improper jointing or curing was done. Also, if cracks expose rebar, it can lead to corrosion stains or spalling at the surface. In summary, rebar’s crack control is structural (preventing failure and large cracks under load), whereas fibers’ crack control is preventive and cosmetic (mitigating fine cracks and surface defects from the start).

4) Tensile Strength and Flexural Capacity

Fiber: Moderately increases the tensile/flexural strength of concrete as a whole, mainly by enhancing its post-crack load capacity and ductility rather than dramatically raising first-crack strength. Adding fibers (especially macro-fibers) to a concrete mix can improve the residual load capacity after cracking – in standard beam tests (ASTM C1609), fiber-reinforced concrete specimens carry significantly more load beyond the initial crack compared to plain concrete. For instance, a certain dosage of macro synthetic fiber can boost the residual flexural strength by ~30–40% relative to plain concrete. However, fibers do not typically double or triple the tensile strength the way adding steel bars can, because fibers are not present in as high a volume or oriented to take all the tensile force. So the direct tensile capacity improvement of FRC is limited – often on the order of 10–40% increase in first-crack strength depending on fiber type and dosage. In practical terms, fibers make the concrete tougher and less brittle, but they are usually not sufficient as the sole reinforcement for high loads. They work well to redistribute stresses and prevent sudden failures (increasing the concrete’s toughness index and energy absorption), but a fiber-only slab will still crack under lower load than a properly rebar-reinforced slab. Thus, fibers are considered a complement for tensile capacity: great for enhancing ductility and controlling cracks after they form, but not a substitute for strong steel reinforcement in load-critical members.

Rebar: Greatly increases tensile and flexural strength of a concrete member in the designed directions, often more than doubling the load capacity compared to plain concrete. Steel rebars have yield strengths commonly in the range of 60,000 psi (~420 MPa) or more, and by placing enough steel cross-sectional area in a member, engineers can ensure the reinforced concrete section will carry the required tension. For example, a rebar-reinforced beam can easily have 100% or more increase in tensile capacity over an unreinforced one, because the steel bars take essentially all the tensile force once cracks occur. Rebar provides a reliable, well-quantified tensile strength contribution – design formulas (ACI, Eurocode, etc.) treat rebar’s strength directly in computing moment capacity. In flexural tests, a rebar-reinforced concrete beam will carry load until the steel yields (often achieving much higher load than the cracking load of plain concrete). Furthermore, rebar imparts significant ductility at the member level: after cracking, the steel can yield and deform considerably while holding the structure together, giving warning before collapse. In short, if you need a concrete element to resist a large bending moment or tensile force, rebar is the dependable way to provide that capacity. Design codes generally require rebar for structural members because of this known performance – fibers, if used, are often not credited with a major increase in allowable design strength (except in some specific fiber-reinforced concrete design approaches). Thus, for primary tensile reinforcement, rebar remains far superior to typical fiber additions in terms of absolute strength provided.

Note: There are high-performance FRC formulations that can reach impressive structural performance (like ultra-high-performance fiber concretes with very high fiber dosages), but in standard practice fibers are used to augment, not replace, the load-bearing role of rebar in critical elements. Always check design codes – most codes do not allow fibers alone to be used for main flexural reinforcement in beams or slabs that carry significant loads.

5) Durability in Harsh Environments

Fiber: Offers durability advantages by reducing crack widths (thus limiting moisture ingress) and by using materials that don‘t rust. Many fibers (polypropylene, polyethylene, polyvinyl alcohol, glass, basalt, etc.) are non-metallic and immune to corrosion, so they won’t degrade or cause staining even in aggressive environments with salts or chemicals. By keeping cracks tight and well-distributed, fiber-reinforced concrete is less penetrable to water and chlorides – it tends to have lower permeability due to the tighter crack network, which means better performance under freeze-thaw cycles and chemical exposure. For example, if fibers hold shrinkage cracks to hairline width, deicing salts or seawater will have a harder time reaching any internal steel or causing expansion. In freeze-thaw conditions, the reduced crack size prevents water from entering and freezing inside, thus minimizing freeze-thaw damage. Also, fibers themselves (if synthetic) are not affected by such cycles. In environments where corrosion of rebar is a major concern (marine structures, coastal pavements, wastewater facilities), using non-corrosive fibers can enhance the long-term durability by eliminating the risk of rust in those reinforcement elements. Additionally, since fibers reduce the risk of large cracks, they indirectly protect any steel that is present in the concrete by preventing cracks that expose steel. Some fibers like polypropylene or PVA also improve resistance to abrasion and impact, which contributes to durability in wear-and-tear scenarios. Overall, fiber reinforcement contributes to durability by creating a tough, crack-resistant concrete that seals itself against environmental attack.

Rebar: While excellent for strength, rebar can be a durability liability if the concrete is not properly detailed or maintained, because steel rebars are prone to corrosion when exposed to water, oxygen, and especially chlorides (salt). In harsh environments (e.g. coastal areas, roads regularly salted in winter, chemical plants), any cracks or thin cover can allow corrosive agents to reach the steel. Rusting rebar expands inside the concrete, which can lead to cracking and spalling of the concrete cover, further accelerating damage. For example, unprotected rebar in a wet, chloride-rich environment might lose a significant cross-section over years; one study notes standard steel rebar can lose ~40% of its cross-sectional area after 20 freeze-thaw cycles in salt water spray. This corrosion undermines the structural capacity and can be dangerous if not addressed. Engineers mitigate this by requiring sufficient concrete cover thickness, using coatings (epoxy-coated or galvanized rebar) or using corrosion-inhibiting admixtures, but these add cost and require careful quality control. Rebar’s durability in harsh conditions thus depends on concrete quality and crack control – if the concrete remains uncracked and low-permeability, rebar can last for decades; but if not, the structure may deteriorate. In contrast, fiber options like stainless steel fibers or synthetic fibers don’t rust at all. That said, properly protected rebar is still used widely in harsh environments (often with added safety factors and protective measures), and it provides the needed strength. But when comparing reinforcement types alone: fibers have an edge in corrosive environments since they either don’t corrode or help reduce cracking that exposes steel. Rebar-reinforced structures in marine or deicing conditions must be designed and maintained carefully to ensure durability over their service life.

6) Labor and Construction Speed

Fiber: Generally simplifies the construction process and can speed up projects, because adding fibers is mostly a batching task rather than a separate construction step. The fibers are typically delivered in bags or bundles and are dosed into the concrete mixer or truck either at the plant or on-site. This means there is no need for crews to spend hours placing and tying steel on site for certain applications. For example, in a slab-on-grade pour, using macro fibers can eliminate the time-consuming process of laying down wire mesh or rebar mats. Contractors have reported significant labor savings – one case replaced traditional rebar mats with fibers in a large slab and eliminated 380 labor hours of bar installation. Less rebar work also means fewer scheduling dependencies (no waiting for steel fixing to finish before pouring). In terms of safety and handling, fiber reinforcement removes the heavy lifting of steel bars and the risk of back injuries from tying rebar. Crews don’t have to carry, cut, or bend steel on site, which can streamline workflow. Quantitatively, one comparison showed that for 100 square feet of slab, using #4 rebar on 12″ spacing required ~2.8 labor hours, whereas a macro fiber dosage needed only ~0.9 labor hours. That kind of reduction can translate to faster completion of concrete pours and potentially reduced labor costs. Additionally, there are fewer concerns about chairing (supporting the steel) or maintaining proper positioning – fibers mix throughout by default. Overall, fiber reinforcement is considered very labor-friendly: you “mix and go,” which often accelerates construction and allows crews to focus on placing and finishing concrete.

Rebar: Involves more labor-intensive and time-consuming steps on a construction project. Before concrete can be poured, the reinforcing bars must be cut (or come pre-cut), placed in the forms or on chairs, and tied together according to the design drawings. This is a skilled task usually performed by ironworkers, and it can be a critical path activity that dictates the schedule. Especially for complex shapes or heavy reinforcement designs, placing rebar can be tedious and slow. Every intersection typically needs to be tied with wire, and ensuring the correct spacing, lap splices, and clear cover adds to the complexity. Large projects might require weeks of work to install rebar cages for foundations or walls. The labor cost for rebar installation can be quite high – in some cases exceeding the material cost of the rebar itself. Moreover, rebar installation is physically demanding and poses some safety risks (cuts from steel, back strain, trips on protruding bars). Because of the intricate work, there is more room for human error – mis-placed bars or improper support can lead to quality issues. All this means that using rebar tends to slow down the construction cycle relative to fiber, which has none of those on-site steps. For instance, if a crew can skip rebar and go straight to pouring with fibers, they might finish a large slab in one day that otherwise would take two (one for setting rebar, one for pouring). There’s also an inspection step: rebar installation typically must be inspected for code compliance (proper size, spacing, cover) before pouring, which can introduce schedule delays if corrections are needed. In summary, while rebar is traditional, from a construction efficiency standpoint it requires significantly more on-site labor and time, impacting the project schedule and cost.

7) Cost Structure

Fiber: The cost profile of fiber reinforcement tends to involve higher material unit cost but lower labor cost, and often a reduction in other expenses. On a per pound basis, polymer or specialty fibers can be more expensive than steel (for example, a few dollars per kilogram for polypropylene fiber versus steel rebar which might be on the order of $0.50–$1 per kilogram). So if one compares raw material weight, fibers are less cost-effective per unit weight than standard rebar. However, fibers are used in much smaller quantities by weight – a typical dosage might be 1–4 kg of fiber per cubic meter of concrete, whereas the equivalent area rebar might weigh much more. Moreover, fibers can eliminate a lot of labor and ancillary costs, as discussed above. When evaluating total installed cost, fibers often come out favorably for applications like slabs-on-grade. There is no need to purchase rebar chairs, no storage of long steel bars on site, and fewer scheduling delays. The cost becomes more predictable as well – it’s essentially the fiber material cost (which is fixed per cubic yard of concrete) and minimal extra labor to add to the mix. Studies and contractor reports have found that using synthetic fiber in slabs can reduce the overall reinforcement cost because the savings in labor outweigh the higher fiber material cost. Additionally, fibers might reduce long-term costs by preventing early-age shrinkage cracks, thereby avoiding repairs or callbacks, which is a lifecycle cost saving not immediately seen upfront. Fiber manufacturers also point out reduced steel price volatility concerns – the price of steel rebar can fluctuate with the market, whereas synthetic fiber prices may be more stable. In summary, fiber reinforcement‘s cost advantage is realized in labor savings and potentially lower maintenance, making it quite cost-competitive for the right projects. It’s often said: the in-place cost of fiber vs rebar is what should be compared, not just the material price per pound.

Rebar: The cost structure of rebar reinforcement is almost the inverse: steel itself is relatively cheap per unit strength, but the overall installed cost is elevated by the labor and time required. Rebar remains one of the most cost-effective reinforcements on a pure material strength basis – per unit weight, steel rebar provides a lot of reinforcement for the price. For large structural projects, buying steel in bulk is economical and usually a small fraction of the total project cost. However, when considering “installed cost,“ one must add the labor of installation, potential fabrication, and the schedule impact. Labor for tying rebar can be expensive, especially in regions with high labor rates or if skilled ironworkers are in short supply. This can make rebar reinforcement of a slab or pavement notably more expensive in practice than an equivalent fiber solution, even if the steel itself cost less than the fiber. Another factor is steel price volatility – global steel prices can swing, affecting rebar cost unpredictably, whereas fibers (often petrochemical-based) have their own market factors. In times of high steel prices, fiber solutions become even more attractive cost-wise. Rebar also incurs ancillary costs: delivery of heavy bundles, crane or hoisting on site, and wastage (off-cuts of rebar that can’t be used). If a design is rebar-heavy, congestion might slow concrete pouring (increasing placement cost) or require expensive higher-strength concrete to flow around bars. Long-term value: rebar certainly adds structural value and may be the only option for load-bearing capacity, so its cost is justified there. But for purely crack control, using a full rebar mesh might be overkill and not the most economical choice. In summary, rebar is cheap to buy but can be costly to install, whereas fibers are costly to buy but cheap to install. When comparing options, it’s wise to compare the total in-place cost and consider factors like construction timeline. Often, a hybrid approach (minimal rebar + fiber) can optimize both material and labor costs.

8) Construction Complexity and Quality Risk

Fiber: Fiber reinforcement makes construction simpler, especially for complex shapes or tight spaces, and generally reduces the risk of errors related to reinforcement placement. Since the reinforcement is just mixed into the concrete, there’s no concern about maintaining proper rebar spacing or cover – the fibers automatically disperse (assuming good mixing practices) throughout the member. This is very beneficial in elements with complicated geometry (curved shapes, thin shells, etc.) where placing traditional rebar might be extremely difficult or impossible. Fibers also avoid reinforcement congestion issues. In heavily reinforced rebar designs, you can end up with so many bars that it’s hard to properly consolidate the concrete (vibrate) or even fit aggregate through the gaps. Fiber reinforcement doesn’t obstruct the concrete mix at all – it is the mix – so you can often achieve high reinforcement density (in terms of crack control) without making concrete placement harder. This reduces the quality risk of honeycombing or voids that sometimes occur with congested rebar arrangements. Additionally, there’s less chance of a critical mistake like a missing rebar or an incorrectly placed bar, which in rebar construction could severely undermine structural performance. However, fiber use isn’t completely without quality considerations: it’s crucial to mix fibers uniformly. Poor mixing can lead to clumping (fiber balls) or uneven fiber distribution, meaning some areas of concrete might end up under-reinforced by fibers. This is why contractors must follow proper dosing and mixing procedures (often adding fibers gradually, using a higher slump or plasticizer to aid dispersion). If done correctly, though, fiber reinforcement has lower inspection and oversight needs – you don’t have to measure cover or check each bar; you mainly ensure the correct fiber dosage was added and mixed well. In sum, for many projects, fibers simplify construction and reduce the risk of human error in reinforcement, as long as the batching is done properly.

Rebar: Rebar reinforcement introduces greater complexity in both design and execution, and with that comes higher risk of quality issues if not managed carefully. Each rebar must be placed according to the structural drawings – if bars are misplaced, omitted, or have insufficient concrete cover, the structure’s capacity and durability can be compromised. For example, if workers set the rebar too close to the surface, it could later corrode; if they space it incorrectly, the member might not achieve its intended strength. There’s also a risk of congestion and constructability problems: heavy rebar cages can be difficult to assemble correctly, and in extreme cases, an overly congested rebar design may prevent concrete from fully encasing the steel, leading to voids or weak zones. Every bend and splice of rebar is a potential point where an error could occur (wrong bend radius, inadequate overlap, etc.). Thus, quality control for rebar is critical – inspection prior to concrete placement is standard to catch any mistakes. Another risk is that rebar placement can be disrupted during the pour; if workers walk on the rebar or if concrete flow moves lightly tied bars, the rebar might shift out of position. This is a known issue if the rebar isn’t securely tied or chaired. In contrast, fibers eliminate those concerns. Rebar construction also typically requires coordination with design to avoid clashes (e.g., rebar leaving enough space for electrical conduits or anchor bolts), adding complexity. In summary, while rebar is very effective, the risk of improper installation is higher – a single misplaced bar might significantly weaken a beam or slab. There have been cases of structural problems traced back to mislocated or insufficient rebar. Therefore, using rebar demands strict adherence to quality practices (skilled labor, inspections). Fiber reinforcement, by virtue of being more foolproof to install, avoids many of these pitfalls. That said, the “failure points“ for fibers, if any, would be things like poor finishing (fibers sticking out if not properly troweled) or using fiber inappropriately where steel was needed. Each method has its considerations, but overall, rebar adds more complexity to construction and relies more on human precision.

What Is the Best Reinforcement for Concrete, Rebar or Fiber?

Choosing between rebar and fiber (or deciding to use both) comes down to the specific needs and goals of the project. Each reinforcement has its strengths, and often the optimal solution is a combination. Here is a simple decision logic:

- If the concrete element must carry significant structural loads or must comply with strict building code requirements for strength: prioritize rebar. For example, primary load-bearing members (beams, columns, suspended slabs in buildings, footings) generally require rebar to safely resist tensile forces. Building codes typically demand traditional steel reinforcement for these elements to ensure proven capacity and ductility. Rebar is the best choice wherever the design is driven by high tensile stresses or where failure of the element would be catastrophic. In short, for structural load capacity – use rebar first.

- If the main concerns are controlling cracking, improving durability, and speeding up construction for a slab or non-primary element: consider fiber reinforcement (or fiber in addition to minimal steel). In cases like ground-level slabs-on-grade, thin concrete toppings, pavements, or shotcrete linings, the goal often is to minimize shrinkage cracking and improve toughness rather than support a heavy load. Here, fiber can often do the job more efficiently. Fiber is also a great choice for enhancing durability in harsh exposure (since it won’t corrode) and for simplifying placement. So for crack control and longevity – fiber may be the better starting point.

- For the highest performance and longest service life, especially in demanding projects, a hybrid approach (fiber + rebar) is often ideal. Using both allows you to get the tensile strength of rebar plus the crack resistance of fibers. Many advanced concrete designs now combine macro synthetic fibers to reduce shrinkage cracks and improve post-crack behavior, together with steel rebar where needed for ultimate strength. For example, an industrial floor might use a moderate amount of rebar around columns or for lifting anchors, but also fibers throughout the slab to control shrinkage and impact cracks – yielding a more durable floor with less steel overall. Hybrid reinforcement can be a “best of both worlds“ solution when budget and design permit.

To make the decision systematically, consider these factors (a short checklist) before choosing reinforcement:

- Structural Loads: What kind of loads will the concrete see – heavy static loads, vehicle traffic, dynamic or impact loads? Heavy tensile/bending loads (like in beams or suspended slabs) lean towards rebar. Light loads or mainly compression with need for crack control (like a slab on grade) might lean towards fibers.

- Exposure Conditions: Is the concrete in a corrosive or freeze-thaw environment? If yes, fibers (especially synthetic or non-corrosive fibers) have an edge in durability, whereas rebar will need extra protection or could shorten lifespan. For mild environments, this is less of a concern.

- Member Thickness & Joint Spacing: Large, expansive slabs or thin sections often benefit from fibers distributed everywhere to control cracking over big areas. Rebar is less effective at preventing distributed shrinkage cracks in wide panels. If you plan wide joint spacing or have a very large pour, fibers can help manage internal stresses better.

- Construction Constraints: Consider site logistics – is there room and time to lay rebar? In complex shapes or congested areas, placing rebar might be impractical, so fiber could solve a lot of headaches. Conversely, if using fiber, ensure the ready-mix supplier can mix it properly. If vibration or formwork access would be hindered by rebar congestion, fiber becomes more attractive.

- Code and Design Specifications: Does your engineer or local code allow fibers as a substitute in your application? Some codes permit fiber for temperature/shrinkage reinforcement in slabs, but not for primary structural capacity. Always check: if the design must be stamped by an engineer, get their input on whether fiber reinforcement is acceptable, and for what portions. Often, engineers will require a certain minimum rebar regardless, especially in structural elements, and might allow fibers to replace wire mesh in slabs, etc.

In summary, use rebar where you must, use fiber where you can – and don’t hesitate to use both when each addresses different needs. A good rule of thumb is: for strength, start with rebar; for crack control and durability, add fiber. If you are ever unsure, consult a structural engineer who is familiar with fiber-reinforced concrete technology so they can evaluate your specific case. The best reinforcement strategy is ultimately the one that meets the project’s structural requirements, durability targets, and budget in the most efficient way.

Does Fiber Reinforced Concrete Need Rebar?

This is a common question when considering fibers: If I use fiber-reinforced concrete, can I eliminate rebar entirely? The answer depends on the structural role of the concrete element. In many non-structural or lightly loaded applications, fibers can be used without any conventional rebar. But in structural, load-bearing members, fibers alone are usually not sufficient to meet design requirements, so rebar is still needed.

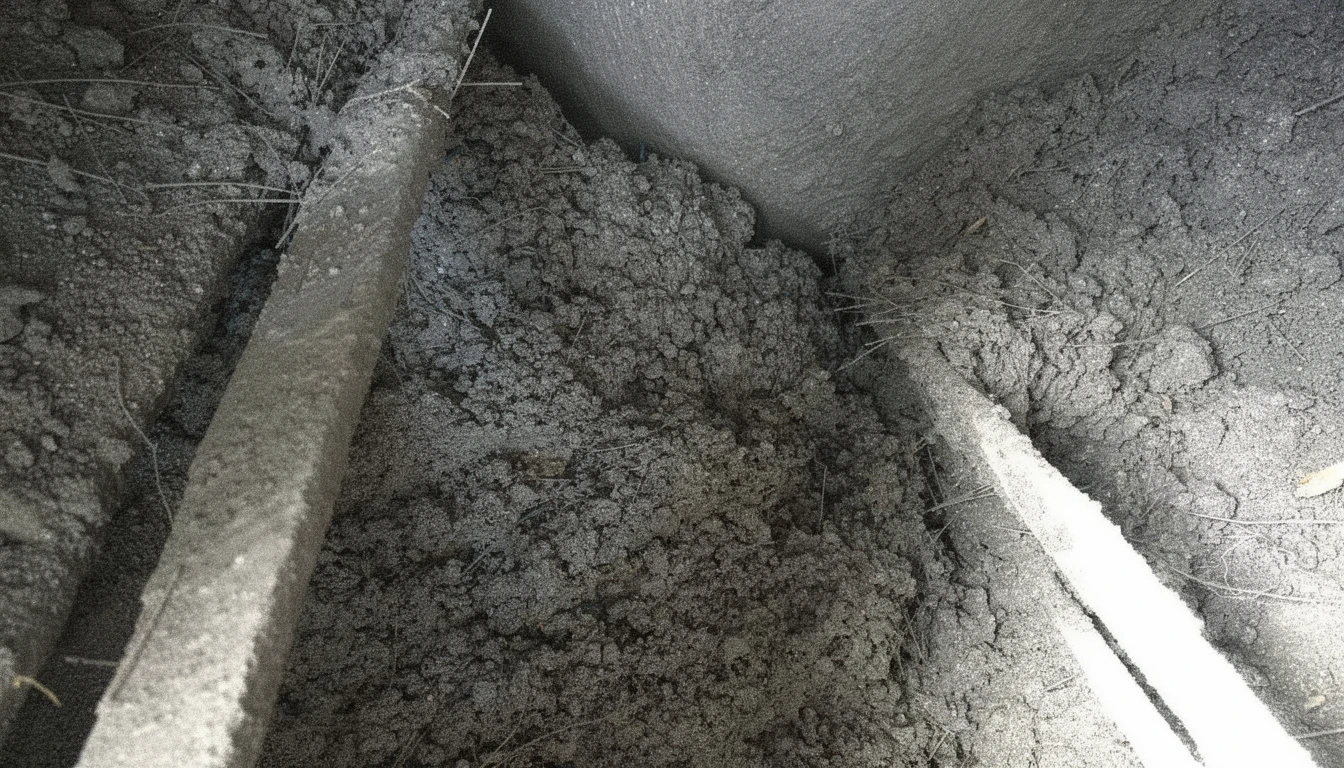

- Non-Structural Scenarios (Fiber Only): For cases like ground-supported slabs-on-grade, sidewalks, driveways, certain precast units, or shotcrete for slope stabilization, a properly designed fiber mix can often replace the need for rebar or mesh. These are situations where the concrete mainly needs shrinkage crack control and some toughness, but not much bending strength. For example, many warehouse and garage floors have been successfully done with fiber reinforcement instead of light rebar mesh, performing well by controlling cracks and carrying the intended loads (which are spread out on the ground). Fibers are also widely used in tunnel linings (shotcrete) and precast pipes or manholes without additional steel – here the fibers provide enough reinforcement for crack control and handling stresses, and there are no big bending moments that would demand rebar. So in slabs and panels that are supported continuously by soil or are mainly designed for durability, fibers may suffice, provided the design is done with fiber data and within code allowances. Always ensure the fiber type and dosage are adequate for the task – e.g., macro synthetic fibers at a high dosage if replacing mesh in a slab.

- Structural Scenarios (Rebar Required): The majority of structural concrete elements still require rebar even if fibers are used. Beams, columns, suspended structural slabs, and any element that carries significant tensile forces must have rebar to meet building codes and safety factors. Fibers alone cannot provide the well-defined tensile capacity and ductile failure mode that rebar provides in these critical elements. For instance, a fiber-only beam would likely crack and fail at a much lower load than the same beam with steel reinforcement, because fibers just can’t carry as much tension in one spot as a thick steel bar can. Building codes like ACI 318 do not allow fibers to replace the required reinforcing steel in beams/columns, etc., for primary reinforcement. So for structural members (especially in safety-critical structures or seismic regions), you will almost certainly need to use rebar. Fibers can be added for extra crack resistance, but not as a substitute for the main steel. As a rule of thumb: if the element is part of the building‘s primary frame or needed for stability, it needs rebar.

In practical terms, fiber-reinforced concrete doesn‘t need rebar when the goal is controlling shrinkage cracks in a slab-on-ground or similar, and the slab isn’t relied on to carry significant load by bending. But if that concrete element is supposed to carry structural loads, you still need rebar. Many projects use a combination: for example, a ground bearing industrial floor might be designed with fibers only (no mesh) if the loads are modest and mostly compressive; but the footing of the building or the columns would have rebar as usual. Another example: residential basement slabs or driveways – fibers can replace the light mesh (saving cost and labor) and perform well for crack control, but the foundation walls with heavy load will have rebar.

Finally, always consult with a structural engineer to confirm if a fiber-only design is acceptable for a given element. Local codes and engineering judgment govern – some jurisdictions might allow fiber in lieu of rebar for certain applications like slab-on-grade, while others might still require a nominal amount of steel. The engineer will consider the loads, the consequences of failure, and the fiber performance data. When in doubt, a hybrid approach (some rebar plus fibers) can be used as a conservative solution: the rebar provides core strength, and fibers handle shrinkage and minor cracks. This way, you get a safe design without completely relying on one method. In summary, fibers can eliminate rebar in non-structural concrete, but fiber-reinforced concrete often still needs rebar for structural strength when the concrete must carry significant tension or must meet code-mandated reinforcement minimums.

Does Fiber in Concrete Replace Rebar?

In general, fiber reinforcement is not a full replacement for rebar in most structural situations. Fibers and rebar play different roles, and rather than one “replacing” the other universally, it’s more accurate to say each can partially substitute for certain functions of the other in appropriate conditions. Here are the key points to understand:

- Fibers cannot completely replace steel rebar in load-bearing structural members. For elements like beams, columns, and elevated slabs that experience high tensile stresses, fibers alone usually cannot provide the required strength and stiffness. Even high doses of macro fibers improve ductility and post-crack behavior, but the ultimate load capacity will still fall short of a properly rebar-reinforced member in most cases. Moreover, design codes generally do not give full credit to fibers for replacing rebar in critical structural components. So if one asks “Can I use fiber instead of rebar in a reinforced concrete beam?” – the answer is no in the vast majority of cases (except some special fiber-reinforced design methodologies with steel fibers in certain precast elements, which are exceptions).

- Fibers can replace traditional steel mesh or serve as the only reinforcement in certain slabs and non-critical sections. One of the most successful applications of fibers is replacing welded wire mesh (WWM) or light rebar grids that are used for temperature-shrinkage crack control in slabs-on-grade. For example, macro synthetic fibers have been used to replace a standard #3 or #4 steel mesh in warehouse floor slabs and parking lots, with the resulting fiber-reinforced slab performing equivalently in crack control. This is now an accepted practice in many areas – design guides exist for fiber in slab-on-grade. Fibers can also replace rebar in thin precast items (like some architectural panels, manhole covers, etc.) where the goal is to prevent cracking and handle handling stresses rather than support large loads. In summary, fiber can act as the sole reinforcement when the structural demands are low and primarily related to shrinkage or minor loads.

- Best practice is often a hybrid approach rather than a pure replacement. Instead of asking fiber or rebar, many engineers are now using fiber and rebar together in optimized proportions. Fibers can take over the role of controlling early cracks and distributing stresses, potentially allowing a reduction in the amount or size of rebar needed, but not eliminating it entirely. For instance, a slab might use fibers to avoid placing a mesh everywhere, but still use conventional rebar in certain areas that see higher moments (like around columns or saw-cut joints). This hybrid design gives a safety net: the rebar handles heavy loads and provides a defined yield mechanism, while fibers keep cracks tighter and enhance durability. Many modern projects find this “fiber + minimal steel” strategy very effective – it can reduce overall steel tonnage (saving cost) while maintaining structural reliability and improving crack performance.

- Clarity: fibers are not a one-for-one substitute for rebar‘s function. Rebar’s function is structural strength (with known yield and ductility), whereas fiber’s function is crack control and toughness. So if someone imagines they can pour fiber concrete everywhere and ignore structural reinforcing – that is a misconception that can lead to unsafe structures. Think of fibers as replacing rebar in the role of crack prevention and secondary reinforcement, but not replacing main structural reinforcement in beams or columns. Even in slabs, when fiber is used to replace mesh, it’s done following design guidelines to ensure load capacity is still met (sometimes the slab might be made slightly thicker or a higher concrete strength is used to compensate, along with the high fiber dosage).

To put it clearly: Fiber in concrete is a great advancement, but it generally does not completely replace the need for rebar in structures. There are specific cases where fiber can replace certain types of steel reinforcement (like mesh) – for example, macro polypropylene fibers can replace welded wire fabric for shrinkage temperature reinforcement in a ground slab, under the right conditions. However, if the slab needs rebar for flexural strength (say a suspended slab or a footing), you cannot remove all the steel just because you added fibers. Always base such decisions on engineering design: manufacturers like Ecocretefiber™ provide data and guidance to help determine when a fiber dosage can replace light rebar or mesh. And remember, a hybrid fiber-rebar design is often the optimum – using each material where it works best, rather than expecting one to entirely take over the other’s job.

Expert Guidance

Deciding on the right reinforcement strategy can be complex, and it’s wise to seek expert guidance to ensure an optimal outcome. Our team of experts recommends a project-specific approach – considering the structure’s load requirements, exposure conditions, and performance goals – to determine whether fiber, rebar, or a combination will serve best. We guide clients through fiber selection (micro vs. macro, synthetic vs. steel fibers), appropriate dosage recommendations, and even mixing and finishing techniques to get the best results with fiber-reinforced concrete. Proper support is key: for instance, we help you ensure fibers are evenly distributed in the mix and advise on any mix design adjustments (like adding a superplasticizer for higher fiber dosages) so that workability and finish quality remain high. If a hybrid solution is suitable, our engineers will also advise how to effectively reduce some rebar by incorporating fibers, without compromising safety – always backed by calculations and reference to standards.

At Ecocretefiber™ (Shandong Jianbang Chemical Fiber Co., Ltd.), we provide comprehensive technical support as part of our service. Our technical team can work with your project engineers to evaluate how fibers can be used in your specific project. We offer assistance in choosing the right type of fiber (for example, micro-fibers for shrinkage crack control or macro-fibers for structural toughness), and we provide design guidance so that any replacement of conventional reinforcement is backed by solid data. We also supply detailed datasheets, example calculations, and even on-site guidance during trial pours. This kind of expert partnership shortens the learning curve – as an example, when you work with Ecocretefiber, our team can suggest dosage ranges for your application and help interpret lab test results, ensuring you reach a working mix design efficiently.

Crucially, we maintain a practical, solutions-oriented approach. The tone of our guidance is straightforward and focused on results – we know construction timelines are tight, so we help integrate our fibers into your project with minimal disruption and clear instructions. Whether it’s advising on finishing techniques (e.g., how to deal with any fibers visible at the surface by proper troweling or clipping) or providing documentation for code officials, our goal is to make fiber reinforcement an easy and beneficial addition for your project.

Credibility and experience: With years of industry experience and a portfolio of diverse projects, our experts have seen what works best in real-world conditions. We’ll be honest about when fibers can replace steel and when they should complement it. Our guidance covers everything from fiber dosage optimization (to avoid waste and ensure effectiveness) to compatibility with other additives, curing practices for fiber concrete, and advice on finishing (so that your fiber-reinforced slab looks as good as it performs).

In summary, you don’t have to make the fiber vs. rebar decision alone. Our Ecocretefiber™ team is here to provide personalized recommendations and support. Contact us for a consultation or to discuss your project requirements – we can help you achieve the ideal balance of strength, durability, and cost-effectiveness in your concrete reinforcement plan. Whether you are a contractor looking to save time or an engineer aiming to improve a design’s longevity, we offer the guidance and high-quality fiber products to make it happen. (For inquiries about fiber selection, dosage, or a quote, feel free to reach out – we also welcome opportunities for distributor partnerships and collaborations.)

Related Products

- Ecocretefiber™ Polypropylene Fibers (Micro & Macro): High-performance synthetic fibers for concrete reinforcement. Our polypropylene fibers come in micro sizes (for controlling plastic shrinkage cracks and surface improvement) and macro sizes (for providing post-crack toughness and replacing light steel mesh in slabs). They are chemically inert, non-corrosive, and disperse evenly in the mix, making them ideal for slabs, pavements, precast elements, and shotcrete applications.

- Ecocretefiber™ Steel Fibers: Rigid, high-tensile steel fibers designed to dramatically increase concrete’s toughness, impact resistance, and load-bearing capacity after cracking. Available in various shapes (e.g., hooked-end, twisted) and lengths, these fibers can partially replace traditional rebar in applications like industrial floors, tunnel segments, and heavy-duty pavements. They provide true composite action with concrete, forming a robust internal reinforcement network that does not rely on placement labor.

- Ecocretefiber™ Glass Fibers (Alkali-Resistant Glass): Specialty AR-glass fibers suited for reinforcement of thin concrete sections and architectural elements (Glass Fiber Reinforced Concrete – GFRC). These fibers won’t rust and offer excellent tensile strength and bonding in the cement matrix. They enhance surface quality and are often used in cladding panels, decorative facades, and any application requiring a lightweight, fire-resistant reinforcement.

(For more information on each product, including dosage guidelines and technical datasheets, please visit our website or contact our technical sales team. Ecocretefiber™ is committed to providing reliable, quality fibers tailored to your project needs, backed by our expert support in implementation.)

Sources:

- R. J. Potteiger Construction – Rebar vs. Fiber Concrete: Choosing the Best Reinforcement

- FORTA Corporation – Concrete Fiber Reinforcement vs. Rebar

- Wellco Industries – Fiber vs. Rebar: Which Reinforcement Wins in Concrete?

- Great Magtech (PrecastConcreteMagnet) – Fiber Reinforced Concrete vs Rebar: Complete Comparison

- WanHong HPMC – Fiber Reinforced Concrete vs Rebar (Blog)

- Ecocretefiber – Polypropylene Fiber for Concrete: Benefits, Dosage, and Applications

- R. J. Potteiger Construction – Rebar vs. Fiber Concrete (Comparison Summary)

- Mid-Continent Steel & Wire – Why is rebar used in concrete?

- Fiber Reinforced Concrete Association (FAQ)

- (Additional industry references and project case studies can be provided upon request.)